Over the summer we published two notes looking at the balance of supply and demand for government bonds. The conclusion was that there appeared to be an excess supply of bonds relative to demand, which could push up yields. This feature is particularly stark for those countries running large fiscal deficits, leaving three potential outcomes for those economies impacted:

- Taxation is increased to reduce deficits and therefore bond issuance

- Government spending is cut to reduce deficits and bond issuance

- Yields rise to a level that brings in enough demand to support the volume of issuance

So far there is limited political appetite to cut spending and increase tax in the most vulnerable countries. But this is likely to change. We need to be prepared for either higher taxation or lower spending, or both, in the countries with the most acute shortfalls.

Changes in taxes and spending will have impacts on the earnings of certain companies. Avoiding these risks may be prudent.

Fortunately, there are also countries whose government finances are strong, where taxes do not need to rise, and who will face less market and consumer pressure.

Which countries have the most work to do?

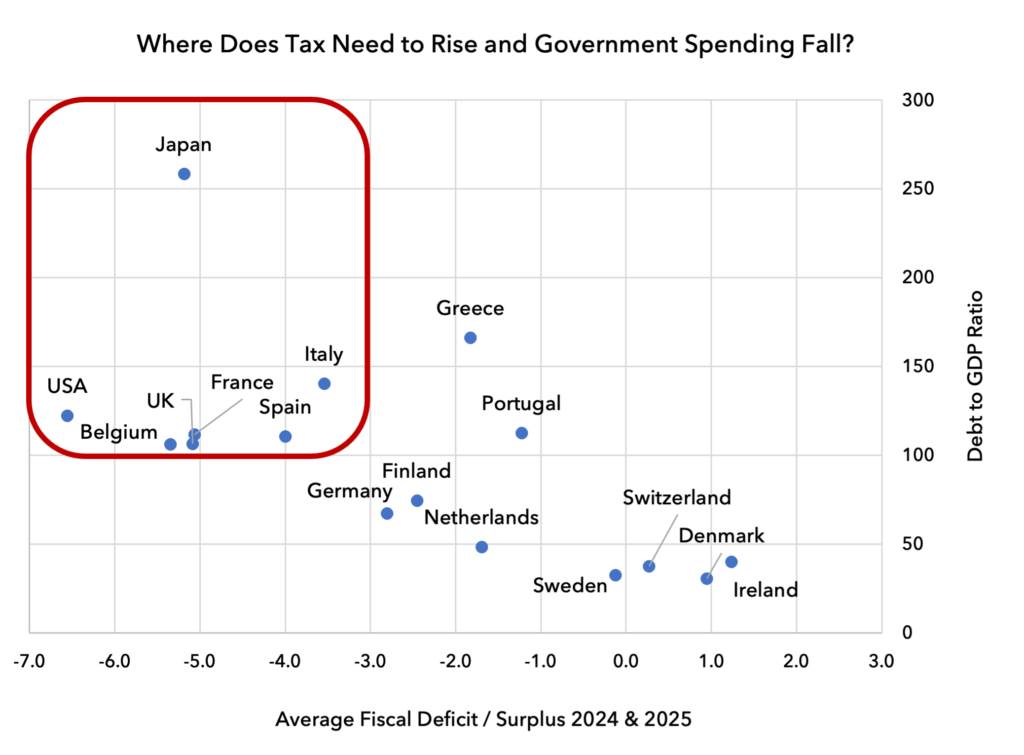

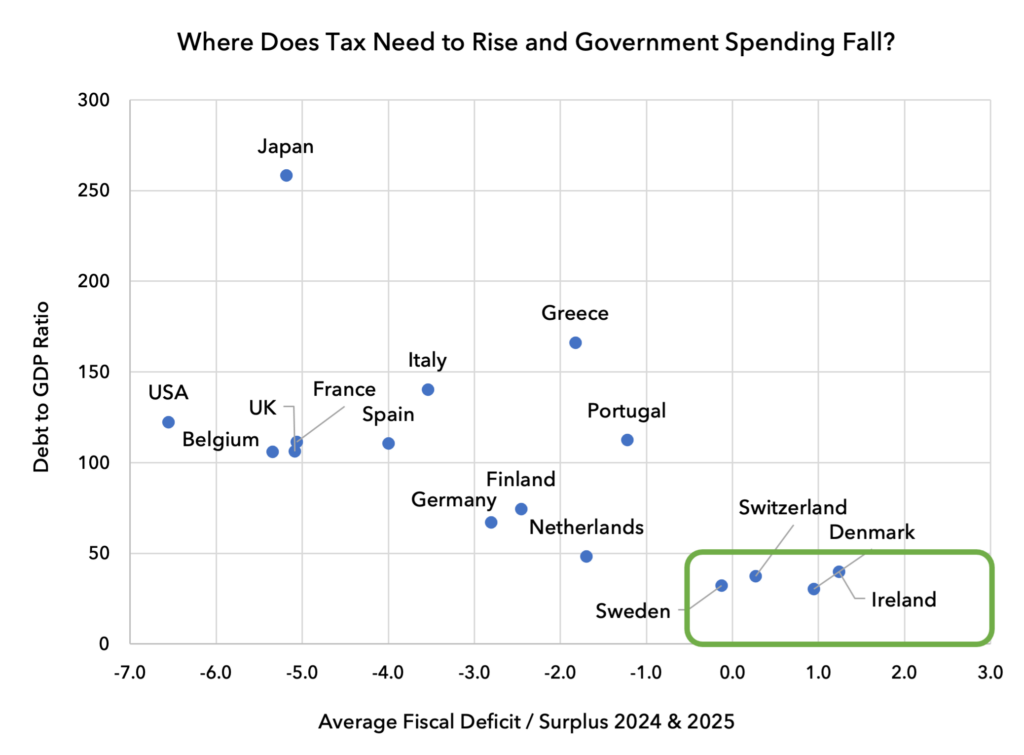

Below we show a chart that has Government Debt to GDP on the Y axis and Fiscal Deficits (or surpluses) on the X axis. The fiscal deficit numbers take an average of forecasts for 2024 and 2025 from the IMF.

We highlight those countries with debt to GDP above 100% and fiscal deficits larger than 3%. The red zone is the area of highest vulnerability. Here there is an increased probability of higher bond yields and pressure to bring taxation and spending into closer balance.

In the Euro area, the most vulnerable countries appear to be Belgium, France, Spain and Italy.

The IMF forecasts that Italy will progressively reduce its fiscal deficit through the 2020’s, nearly eliminating it by 2028. But Belgium, France and Spain are not expected to see much improvement.

The UK and Japan are seen as very marginally trimming their deficits in the later years of this decade. The US is forecast to continue to run a 6.8% deficit even in 2028.

For European countries in the red zone, we may need to be prepared for higher bond spreads in their debt securities relative to German Bunds in the coming years. This will marginally increase the relative cost of capital in these countries’ equity markets, potentially justifying slightly lower ratings, all things being equal.

For the UK and US, bond yields are also set to stay high unless fiscal positions are improved. For Japan, we should prepare for significantly higher bond yields and potentially further currency weakness.

The need to increase the tax take

Whilst there is very limited political appetite to address deficits today, the bond market could change the electorate’s thinking and therefore politicians’ thinking. In the Sovereign Debt Crisis of 2012 it was remarkable how market pressure changed the political reality on the ground in the countries affected.

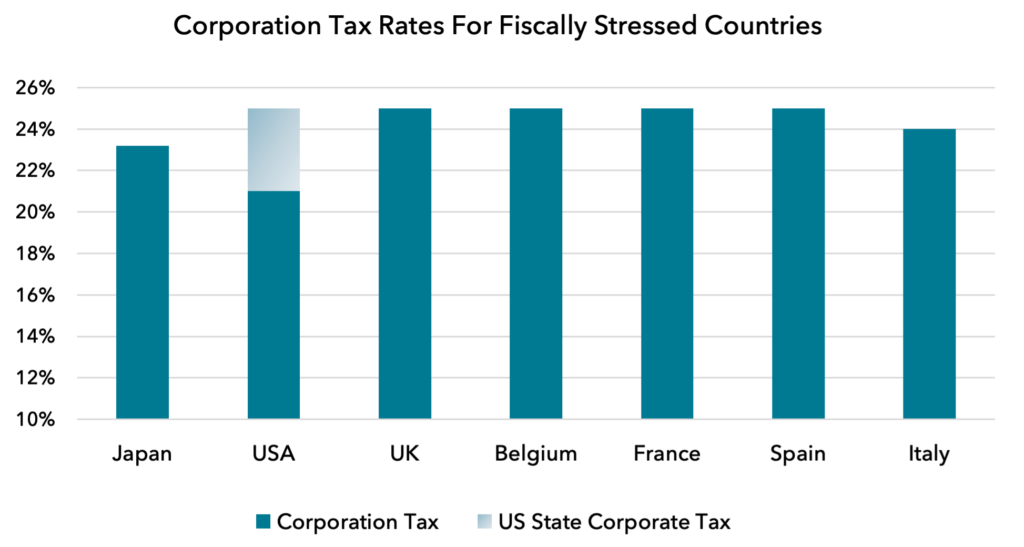

Should we be expecting changes to headline corporation tax? Probably not, because it is relatively harmonised across these red zone countries, as we show below.

Once adjusted for US states’ implementation of corporation tax, the US tax level is not so different to its peers.

It could be expected that Italy and Japan may marginally increase their corporate tax take in due course, but there are no outliers. This makes it less likely that we will see major change to headline corporation tax, at least in the first instance.

Corporation tax harmonisation impacting low tax jurisdictions

Recent years have seen stronger moves to harmonise corporation tax in an effort to minimise jurisdictional arbitrage. The OECD has been working hard to institute its idea of a minimum tax of 15% for large companies. In 2021 it secured a provisional agreement from 136 countries representing 90% of the global economy to this effect. On 11 October 2023, the OECD published an international treaty drafted by these countries to codify the agreement.

It is not clear which countries will end up signing the treaty into law. Brazil, Colombia and India have reservations. And, importantly, it is not known if the US will sign and ratify the treaty. But despite these reservations, the direction of travel is clear. Large tax arbitrage opportunities are not likely to last.

From a European perspective, this is very relevant for Ireland and to a lesser extent Hungary. Hungary has a corporation tax of 9%, with Ireland at 12.5%, compared to a typical EU corporation tax rate of 25%. Ireland’s ultra-low tax rate has provided extraordinary benefits. Its debt to GDP has collapsed from 125% to 45% in a decade and its finances are now so strong that the country is planning to launch a sovereign wealth fund.

Whilst Ireland’s fundamental position is solid, its fiscal position is hugely boosted by corporation tax receipts. We do not expect this to last. There is no incentive for the EU to allow such a significant arbitrage any longer and so we expect Irish corporation tax to move into line with the rest of Europe at some point this decade. This should be viewed as a potential headwind for the economy that is yet to crystallise.

Irish company earnings are also discounting this low tax rate, so a move higher in tax rates would amount to a large free cash flow adjustment. Today we do not own any Irish-listed equities.

Closing loopholes

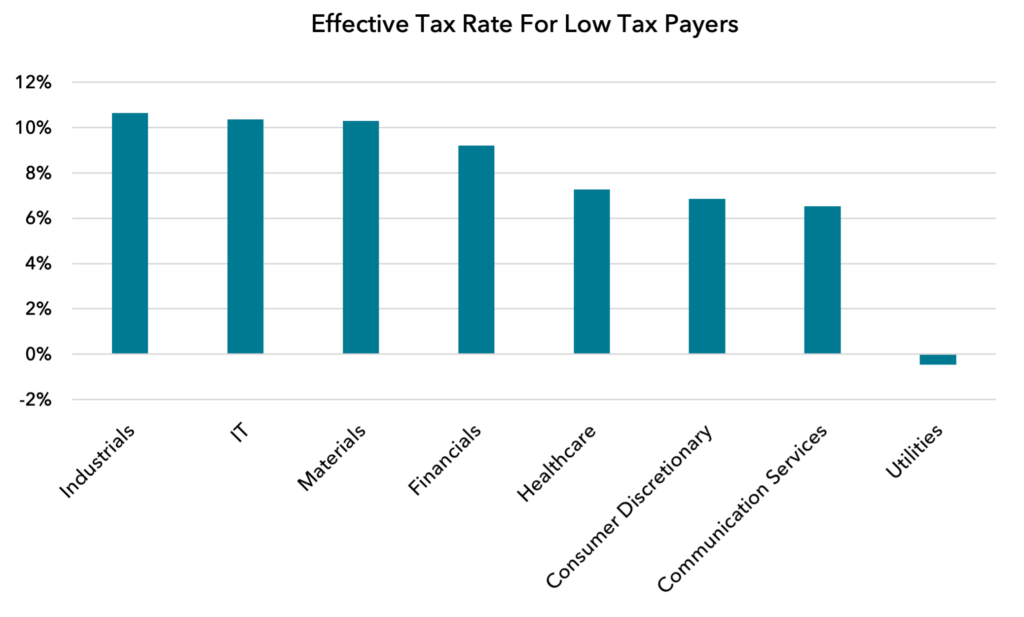

Our “red zone” of fiscally stressed countries may not see large changes to corporation tax, but there may be some changes at the industry level. The US in particular has incredibly variable tax rates for different companies. Some individual companies and industries have been more successful than others in limiting taxes paid, through effective lobbying. Ultra-low tax payers may be vulnerable as tax enforcement is strengthened and loopholes closed.

In the Inflation Reduction Act, there is a minimum 15% corporation tax rate for those companies earning more than $1bn in adjusted income. The final rule on this provision is due later this year.

Tax Notes, an independent non-profit publisher of tax analysis, has identified companies most at risk from this new minimum tax provision. It has produced a list of 90 companies whose tax rate is the furthest below 15%.

Below we group these 90 companies by sector and show the average tax rate of these low tax payers. Utilities clearly stands out, comprising 21% of all companies on the vulnerable list, and the average tax rate is negative. This cannot last.

In the other sectors, Tax Notes identifies some well-known company names that appear vulnerable.

Within Technology, AMD, Nvidia and Micron pay effective tax rates of 0.7%, 4.7% and 6.4% respectively.

In Consumer Discretionary, Amazon pays 7.9%, Ford 7.7% and GM 6.6%. MGM pays just 1.6%.

In Communications Services the Telecoms appear vulnerable. Charter, T-Mobile and AT&T pay only 1.4%, 2.5% and 4.7%.

Whilst we are interested in some of the EU Telecoms companies, we exited our position in Deutsche Telekom earlier this year. T-Mobile USA, which is majority-owned by Deutsche, has a few potential threats in front of it. A change in tax rates is one such threat and would be significant for its FCF and dividend-paying capacity.

Elsewhere in Communications, Fox and Netflix are also low payers, at 7.3% and 9.1% respectively.

Surprisingly, Berkshire Hathaway’s effective tax rate is very low, at 5.7%. This may be partly due to its utility assets, but either way it should be viewed as a potential risk.

One way or the other, the pressure on the public purse is set to be powerful enough for some of these loopholes to be closed over time. This could amount to a notable reduction in free cash flow and therefore valuation for companies impacted.

In Europe, corporate lobbying is not as powerful in manipulating taxes paid, and effective tax rates are broadly more similar at the industry level. Within our own research process we are increasing scrutiny of the effective tax rates paid, and we will be keen to avoid any egregious under-payers of tax, particularly in countries where finances are tight.

Carried interest

The UK’s Labour Party has proposed closing the private equity loophole that allows for bonuses to be paid as a capital gain instead of income. President Biden proposed the same thing in his last election campaign but policy has not materialised. There is a debate about the effectiveness of closing this loophole in a single jurisdiction, but we should not rule out a coordinated attempt by Western governments to extract more tax from private equity in the coming years.

Windfall taxes

We have already seen windfall taxes applied to the oil industry and we expect this to continue. Since these taxes are applied based on the geographical source of production, and most large oil companies are geographically diversified, this has not had a huge impact on the free cash flow of oil companies. The UK’s windfall tax, for example, applies to the North Sea, itself not a large production area any longer for the major oil companies.

Windfall taxes on oil also amount to a form of oil supply control. Oil companies will let production scale back where taxes are punitive. As a result, we do not believe windfall taxes derail the investment case for the sector.

Banks are also increasingly being targeted for windfall taxes. Spain launched new taxes in 2022 with Italy joining this summer, albeit with some confusion on the implementation. Holland has also increased an existing tax.

Given our views on rates staying high and the impact this will have on government and consumer finances, we believe it is appropriate to expect elevated taxes on banks in the coming years.

Cutting spending

Whilst a Democrat administration is more likely to raise taxes, the Republicans are more likely to try to cut spending.

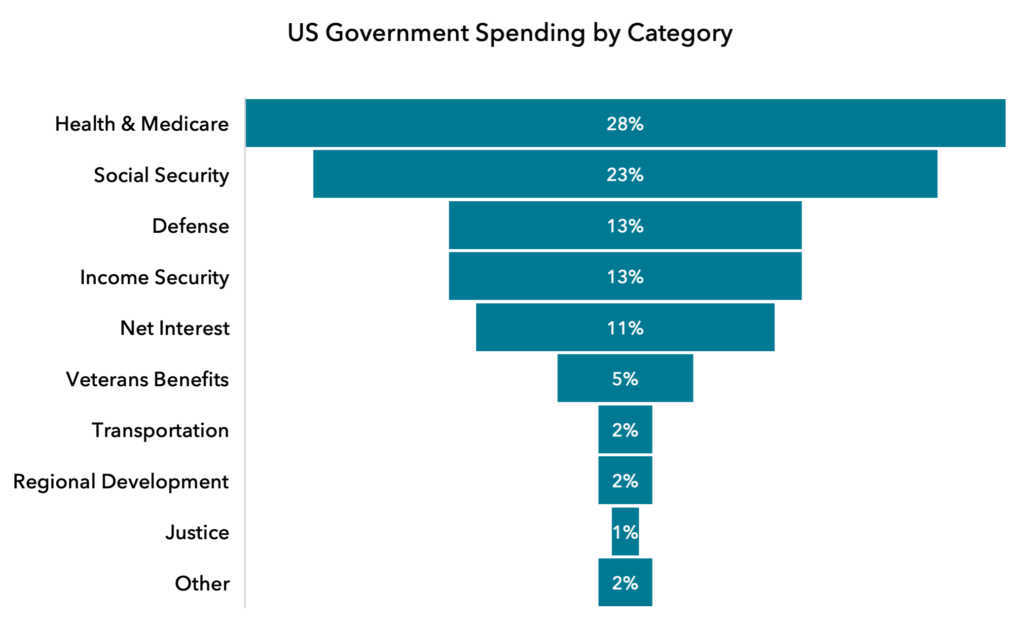

Health, Social Security and Defense are the largest components of US Government spending, as we show below.

In Defense, the US Government may seek to reduce spending, but the geopolitical reality is not allowing for it yet. Social security is another area where an adjustment will be needed, but it remains politically difficult. This puts more pressure on other areas.

Healthcare is an easier target politically and therefore is more vulnerable. Drug pricing reform has already begun. On 29 August the Biden administration announced the first 10 drugs subject to Medicare price negotiations, with lower prices starting in 2026. The initial set of drugs was chosen from the top 50 eligible Medicare Part D drugs that have the highest total expenditure. The first 10 drugs accounted for $50.5bn, or 20%, of Medicare Part D drug costs.

Announcing the news, Joe Biden’s comments underline the political reality: “Big Pharma is charging Americans more than three times what they charge other countries simply because they could. I think it’s outrageous.”

Many European pharmaceutical companies have high percentages of revenue in the US. Navigating this growing political intervention will be difficult. We prefer pharma companies with lower percentages of Medicare revenue and lower drug re-pricing risk.

Whilst the pharma industry is intensely fighting these proposals, we expect subsequent administrations to continue trying to extract savings in Healthcare, because there is no alternative target of similar size.

Clean energy risks

Clean energy stocks have performed badly in 2023, particularly companies exposed to offshore wind. Offshore wind projects typically require governments to set minimum prices per megawatt hour, in order to attract private sector bids. Because lead times on projects are long, many contracts for projects due to come online were set at a time when the cost of capital and the cost of material and equipment was much lower. This has rendered certain projects financially unviable and is putting some operators in financial peril.

Despite the sharp increase in costs, the UK and certain US state governments have not increased pricing sufficiently to attract bids in recent power auctions. The UK had a high profile auction recently that attracted zero bids.

Orsted, the Danish operator of wind farms, recently failed in its appeal to the US regulator in New York for higher rates for an offshore wind project.

One reason New York State and the UK have not lifted prices is fiscal stress. There is insufficient money available. This means we need to be prepared for a slower roll-out of certain green technologies in the coming years.

Clearly, those clean energy sources that require no state guarantees and lower capital costs will continue apace. But more expensive renewable energy categories, in particular offshore wind, are set to have a slower roll-out in those countries that do not have the fiscal space, like the UK and the US. This may put downward pressure on revenue projections for companies selling into those areas.

Individual tax changes

The consumer is already under pressure from high interest rates and high energy prices. Governments on both the left and the right are keen to state that they want to minimise tax increases for working people. But stealth tax increases are starting. In the UK, income tax and national insurance thresholds are frozen from 2021 levels until 2027-2028, despite high wage inflation. Rising wages push large numbers of the population into higher tax rate tiers, sharply increasing the Government’s tax take.

It has been calculated by the Institute of Fiscal Studies that this freeze of tax thresholds is equivalent to raising the basic and higher rates of income tax by six percentage points.

In the US, as the presidential election shapes up, it will be interesting to see if President Biden re-launches his plan to increase taxes for ultra-high earners.

The combination of tax increases – whether by stealth or not – with high interest rates and energy costs makes it hard to see upside surprises emanating from the consumer in the medium term.

The impact of tax changes on valuations

All things being equal, higher taxes diminish cashflow, lowering valuations. The higher a company’s valuation, the longer duration the assessment of future cashflows, making the company more vulnerable to valuation compression from any change in the expectation of those cashflows. Value stocks ought to be more defensive.

Where are the safe jurisdictions?

At the start of the note we identified our red zone countries, those where debt to GDP is high and fiscal deficits are high. The UK, US, Japan, Italy, Spain, France and Belgium are the most in need of raising taxes or reducing government spending.

But what about those countries at the opposite end of the spectrum; those in the green zone that have debt to GDP below 50% and run near-balanced budgets or fiscal surpluses?

Switzerland, Denmark and Sweden stand out well in this respect. There should not be a strong need for these countries to raise taxes or cut spending this decade.

As discussed, Ireland is a special case. It appears strong, but its fiscal position is inflated by corporation tax receipts which may not be permanent.

The special case of Norway

Norway is not on the chart above because it does not fit on the scale. It will run an average fiscal surplus of 25% of GDP in 2024 and 2025. The Government nominally does have some debt at 38% of GDP or approximately $200bn, but this is dwarfed by its sovereign wealth fund of $1.5tn. Norway is unique globally and stands as the world’s safest jurisdiction against the threat of market-forced tax increases.

Our country breakdown

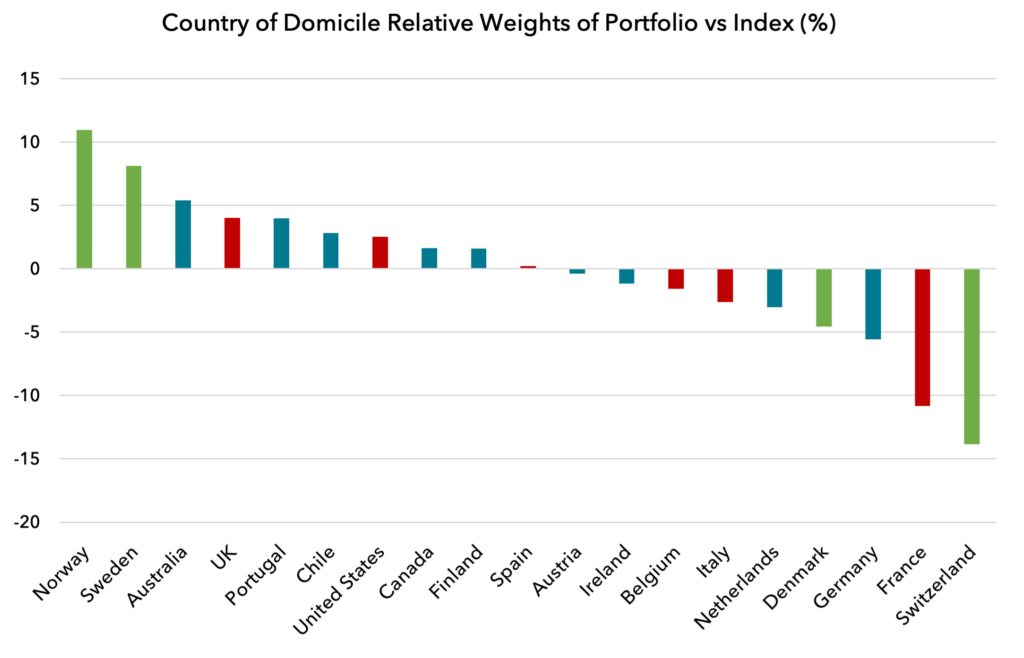

Below we show our active country weights versus the benchmark for our investment portfolio. Here we are using country of domicile as the definition, with red and green zone countries shaded.

It appears that we have an overweight to the UK, which comes from our position in Shell. Whilst Switzerland is in a strong fiscal position, we are significantly underweight. This is a function of the high valuation of many Swiss companies.

The portfolio has large overweight positions in green zone countries like Norway and Sweden and some underweights in the red zone countries of France, Italy and Belgium.

Clearly the portfolio is not run on the basis of country risk. Individual stock fundamentals will always outweigh country effects: there will always be companies where the combination of valuation, operational momentum and balance street strength will offset country risk considerations.

In recent decades, it was the emerging markets that were exposed to pressures from government finances. In developed markets, outside the Sovereign Debt Crisis of 2010-2012, government finances were not seen as particularly relevant for returns.

But we believe this is starting to change. The strength or weakness of government finances is likely to be an important feature for returns this decade. Being prepared for potential vulnerabilities either from market pressure or from government action can hopefully reduce risk and add defensiveness to portfolios in the coming years.

Sources:

IMF Database, US Department of the Treasury, Tax Notes, Strategas, Eurostat, Norges Bank, MSCI, Bloomberg, Lightman Investment Management

Legal

Disclaimer

This communication and its content are owned by Lightman Investment Management Limited (“Lightman”, “we”, “us”). Lightman Investment Management Limited (FRN: 827120) is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (“FCA”) as a UK MiFID portfolio manager eligible to deal with professional clients and eligible counterparties in the UK. Lightman is registered with Companies House in England and Wales under the registration number 11647387, having its registered office at c/o Buzzacott LLP, 130 Wood Street, London, United Kingdom, EC2V 6DL.

Target audience

This communication is intended for ‘Eligible Counterparties’ and ‘Professional’ clients only, as described under the UK Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (“FSMA”) (and any amendments to it). It is not intended for ‘Retail’ clients and Lightman does not have permission to provide investment services to retail clients. Generally, marketing communications are only intended for ‘Eligible Counterparties’ and ‘Professional’ clients in the UK, unless they are being used for purposes other than marketing, such as regulations and compliance etc. The Firm may produce marketing or communication documents for selected investor types in non UK jurisdictions. Such documents would clearly state the target audience and target jurisdiction.

Collective Investment Scheme(s)

The collective investment scheme(s) – WS Lightman Investment Funds (PRN: 838695) (“UK OEIC”, “UK umbrella”), and WS Lightman European Fund (PRN: 838696) (“UK sub-fund”, “UK product”) are regulated collective scheme(s), authorised and regulated by the FCA. In accordance with Section 238 of FSMA, such schemes can be marketed to the UK general public. Lightman, however, does not intend to receive subscription or redemption orders from retail clients and accordingly such retail clients should either contact their investment adviser or the Management Company Waystone Management (UK) Limited (“Waystone UK”) in relation to any fund documents.

The collective investment scheme(s) - Elevation Fund SICAV (Code: O00012482) (“Luxembourg SICAV”, “Luxembourg umbrella”), and Lightman European Equities Fund (Code: O00012482_00000002) (“Luxembourg sub-fund”, “Lux product”) are regulated undertakings for collective investments in transferrable securities (UCITS), authorised and regulated by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF) in Luxembourg. In accordance with regulatory approvals obtained under the requirements of the Law of 17 December 2010 relating to undertakings for collective investment, the schemes can be marketed to the public in Luxembourg, Norway, Spain, and Republic of Ireland. Lightman, however, does not intend to receive subscription or redemption orders from any client types for the Lux product and accordingly such client should either contact a domestic distributor, domestic investment advisor or the Management Company Link Fund Solutions (Luxembourg) S.A. (“Link Luxembourg”) in relation to any fund documents.

Luxembourg umbrella and Luxembourg sub-fund are also approved for marketing to professional clients and eligible counterparties in the UK under the UK National Private Placement Regime (NPPR). UK registration numbers for the funds are as follows: Elevation Fund SICAV (PRN: 957838) and Lightman European Equities Fund (PRN: 957839). Please write to us at compliance@lightmanfunds.com for proof of UK registration of the funds.

Luxembourg sub-fund is also approved for marketing to qualified investors in Switzerland, within the meaning of Art. 10 para. 3 and 3ter CISA. In Switzerland, the representative is Acolin Fund Services AG, Leutschenbachstrasse 50, 8050 Zurich, Switzerland, whilst the paying agent is NPB Neue Privat Bank AG, Limmatquai 1 / am Bellevue, 8024 Zurich, Switzerland.

Accuracy and correctness of information

Lightman takes all reasonable steps to ensure the accuracy and completeness of its communications; we however request all recipients to contact us directly for the latest information and documents as issued documents may not be fully updated. We cannot accept any liability arising from loss or damage from the use of this communication.

Wherever our communications refer to a third party such as Waystone, Link, Northern Trust etc., we cannot accept any responsibility for the availability of their services or the accuracy and correctness of their content. We urge users to contact the third party for any query related to their services.

Important information for non-UK persons (Including US persons)

This communication is not intended for any person outside of the UK, Switzerland, or the European Economic Area (EEA). Lightman or any of the funds referenced in this communication are not approved for marketing outside of the UK, Switzerland, or the EEA. All such persons must consult their domestic lawyers in relation to services or products offered by Lightman.

Risk warning to all investors

The value of investments in any financial assets may fall as well as rise. Investors may not get back the amount they originally invested. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance. Potential investors should not use this communication as the basis of an investment decision. Decisions to invest in any fund should be taken only on the basis of information available in the latest fund documents. Potential investors should carefully consider the risks described in those documents and, if required, consult a financial adviser before deciding to invest.

Offer, advice, or recommendation

No information in this communication is intended to act as an offer, investment advice or recommendation to buy or sell a product or to engage in investment services or activities. You must consult your investment adviser or a lawyer before engaging in any investment service or product.

GDPR

Lightman may process personal information of persons using this communication. Please read our privacy policy.

Copyright

This communication cannot be distributed or reproduced without our consent.