- Sovereign debt pressures are likely to remain a key theme in markets in the coming years, including in parts of Europe

- But despite this and the perceived threat of Trump, we see tactical reasons for optimism for Europe

- We expect European equities to outperform the US in 2025

Sovereign debt fragility in some countries

Market crises often result from a build-up of imbalances, typically excess leverage. Today there is not an obvious imbalance in the consumer or corporates in most of the developed world – the major imbalance is in government debt and the deficits in certain countries.

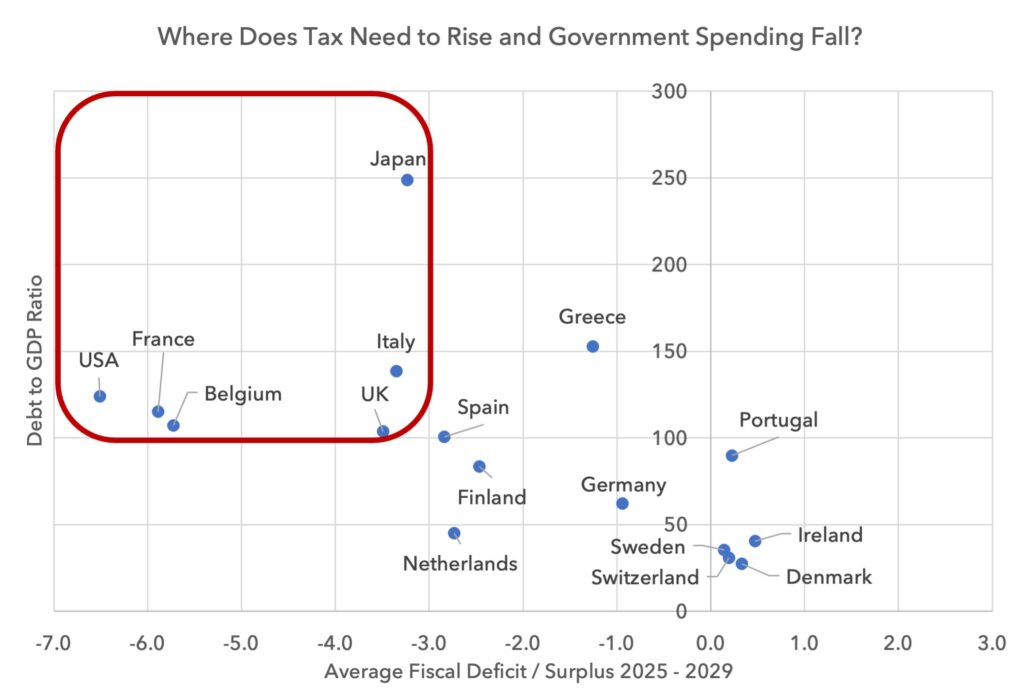

Last year we wrote notes on this subject, and below we have updated some of the charts focusing on debt sustainability. We use the latest data from the IMF Fiscal Monitor Database. In the chart below we show expected fiscal deficits and debt to GDP for advanced economies. Countries in the red zone are where we would expect bond market pressure to come first.

France, as we all know, is already facing this pressure. High deficits with high debt to GDP and a rising debt trajectory are the warning signs, with political inertia to fix the problem acting as the trigger.

The French political problems that began in June have acted as the catalyst for weakness in French sovereign debt. There is not yet the political will in France to make changes, and this is a problem for markets. France has a weak starting point, yet the population at large does not recognise the need for action. There are some similarities to Greece in 2010 and 2011. The Greek population did not accept the need for reforms in the early part of their crisis, but they were forced by market pressure to change their minds.

Given the political impasse in France, it is likely that market pressure will continue. Belgium has almost identical debt and deficit metrics and so may also see bond spreads widen.

The UK and Italy are fragile but at least both countries have high political sensitivity to their respective bond markets. Japanese bond yields also continue to climb.

On the more positive side, Spain’s position has improved a little, whilst Portugal continues to recover sharply. Greece also continues to improve, showing that recovery can come from a deeply distressed starting point. Greek debt to GDP hit more than 200% in 2020 and is set to be 150% in 2025 and less than 140% in 2029.

Why is this relevant for equity markets?

Large deficits and high debt to GDP are more likely to lead to higher yields, all things being equal. This increases the competition for capital and ought to put more pressure on the valuation of other securities. A value bias in equities should provide a higher degree of protection in this circumstance. Within sectors, domestic financials tend to be most vulnerable to rising bond spreads.

Comparing the US to France

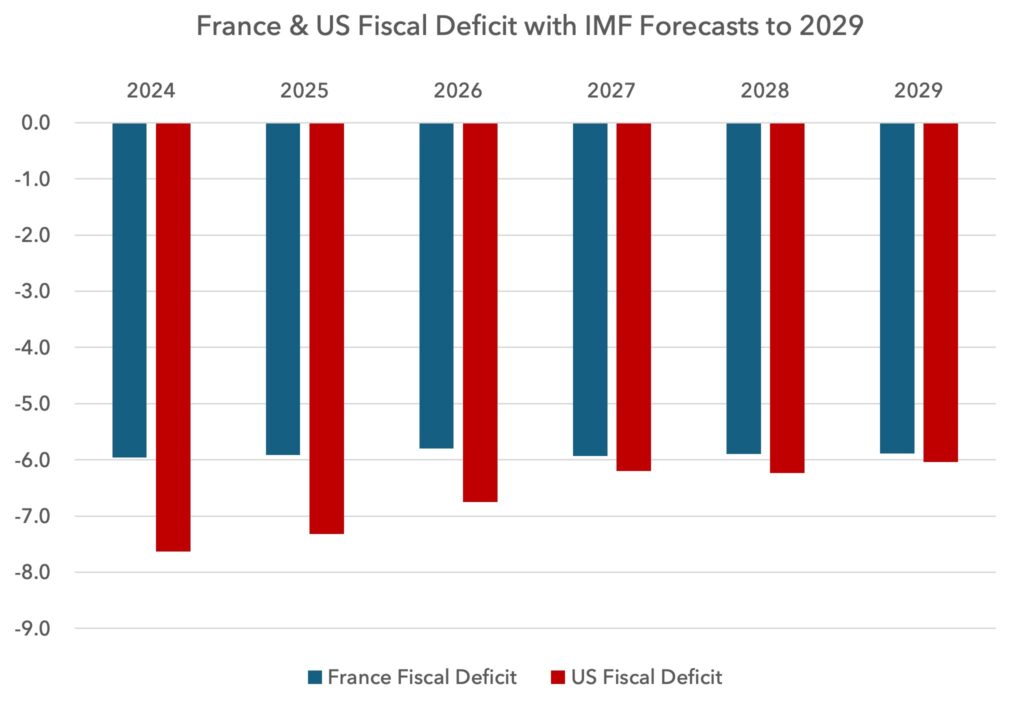

As is noticeable in the fiscal chart above, the US position is weak.

Below we compare the US with France and show their current and expected fiscal deficits out to 2029. The US is clearly in a worse fiscal position than France.

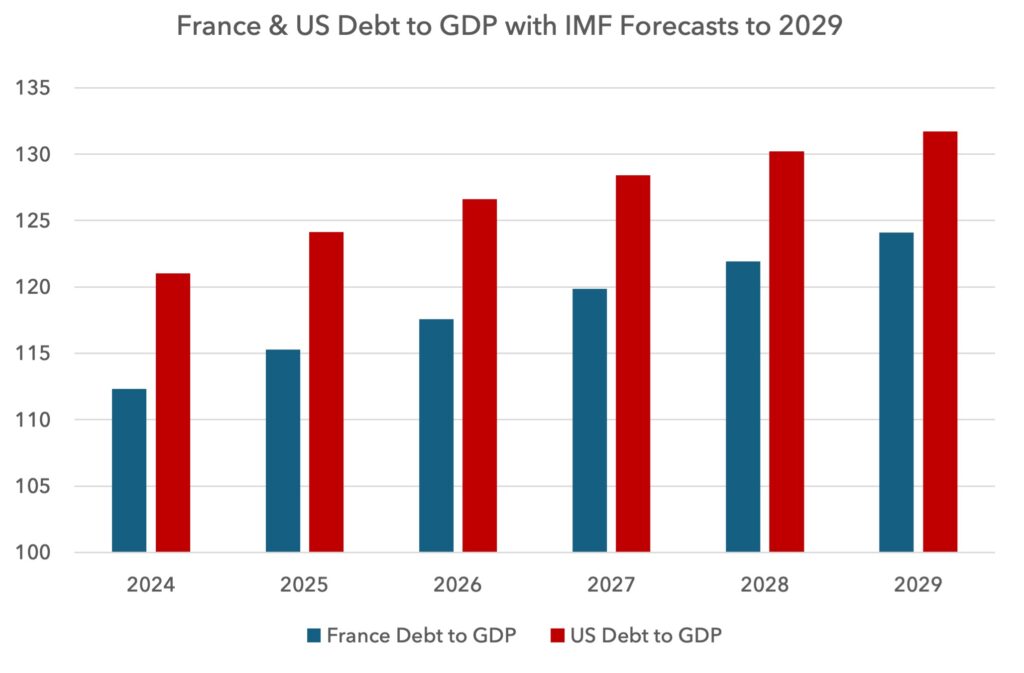

Below we compare the debt to GDP numbers for the two countries. Once more the US is in a worse position.

Tactical relief for US Treasuries

Despite these weak fundamentals, there are some reasons why we could see tactical relief in the short term in US Treasuries. Scott Bessent, the new appointee for Treasury Secretary, is acutely aware of the fragility of US government finances. He intends to improve the situation with his “3 arrows” policy. This is to lift trend growth to 3% from 2% via deregulation, tax cuts and reshoring of manufacturing; lift US oil production by 3 million barrels a day to cut energy costs and reduce inflation expectations; and cut the deficit from 7% to 3% by lifting growth and cutting government spending.

The Fed is also likely to end Quantitative Tightening in Q1 2025. The current pace of Treasury run-off of $25bn per month will drop to zero, providing some support.

The US will also hit its debt ceiling during the first quarter of 2025 and this will mean the Treasury will stop issuing bonds and draw down some of the liquidity from the c.$800bn balance sitting in the Treasury General Account. This will amount to a liquidity injection in markets during Q1 2025 of $200-400bn, adding a potential backstop to US Government bonds.

We also have the prospect of DOGE, the Department of Government Efficiency, and the potential for significant spending cuts that could improve US finances.

But structural problems may return

All of these conditions ought to keep a lid on the US bond market in Q1 2025 and may act to support markets. But once the debt ceiling is lifted, US debt issuance will ramp up again. The Treasury General Account will also need to be built back up, and the pressure will be on for the US to show fast improvements in its fiscal position.

In the background, other pressures are building that may act to push US yields higher later in 2025.

In recent years the Fed has mostly issued T-Bills. This has helped lower bond yields at the long end of the yield curve. But the current split of issuance is so imbalanced that more longer dated bonds will need to be issued and the increased supply will act to push up longer dated yields.

We also continue to see lower appetite for US Treasuries from large sovereign buyers like China. The latest Treasury International Capital (TIC) data shows continued Chinese selling. China has gone from a $1.1tn position to $730bn over the last four years.

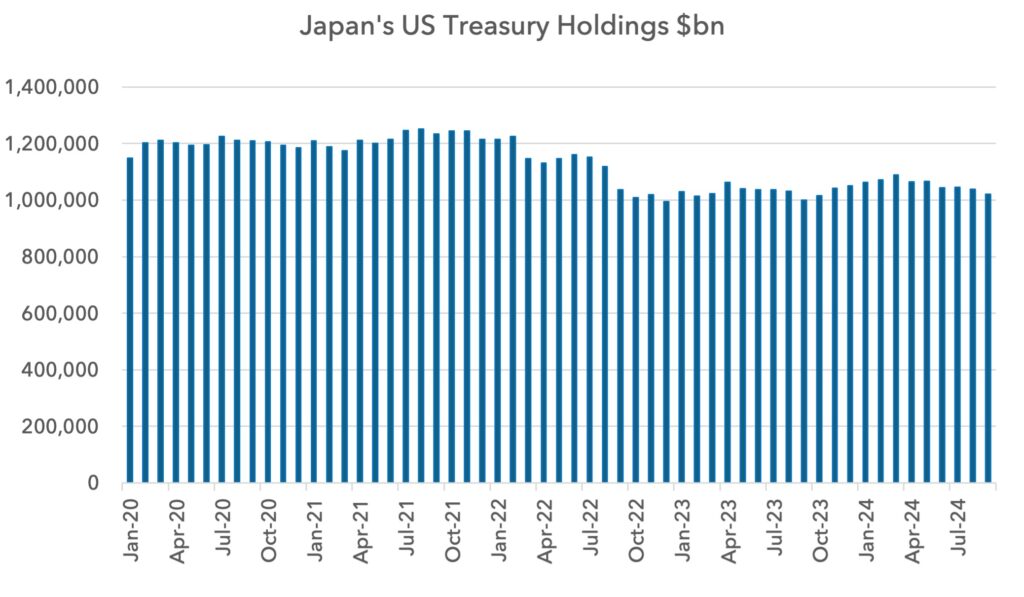

Japan has seen a dip in its Treasury holdings but it has had a more stable position over the last two years.

Japan has seen a dip in its Treasury holdings but it has had a more stable position over the last two years.

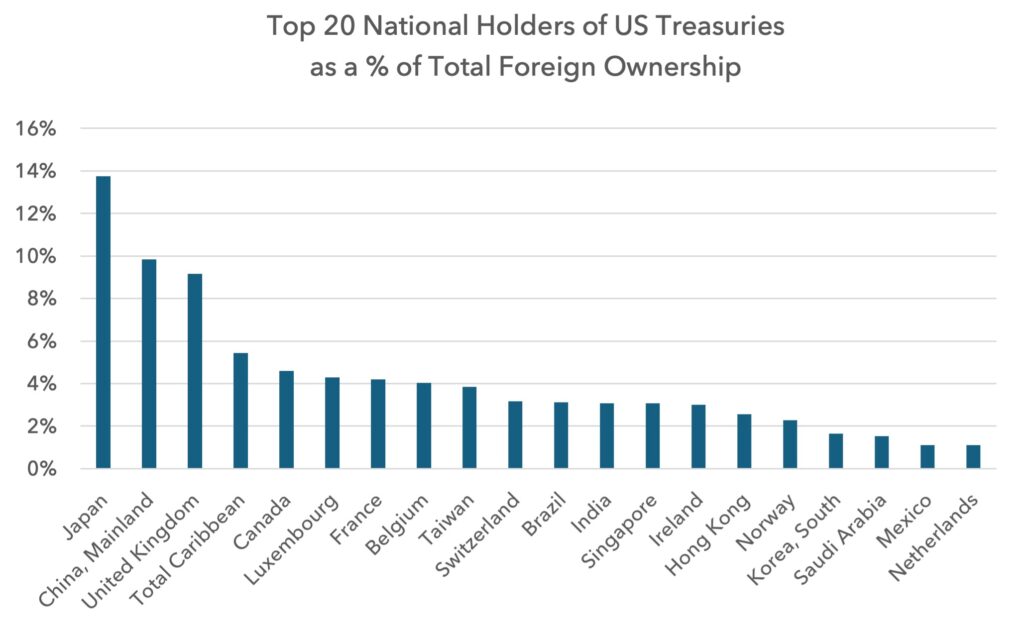

Of course, other countries can pick up the slack, but these two countries are the two largest foreign holders, as we show below.

Of course, other countries can pick up the slack, but these two countries are the two largest foreign holders, as we show below.

Japan’s rising interest costs require more capital. The more Japanese bond yields rise, the more capital will be required. This has to be found somewhere, and a repatriation of foreign holdings will likely provide part of this funding, which might demand more selling of Japan’s US Treasury holdings over time.

What does this mean for European equities?

French bond market pressure will likely continue. This view argues against holding French financials for the time being, be it banks or insurers. It would also suggest some caution against holding aggressive positions in Eurozone financials. We continue to avoid any banks or insurance companies in the “red zone”.

But this is different to 2011-2012. The ECB has multiple backstop programmes and Europe can issue joint bonds, backed by the entire Eurozone. Greece and Portugal have also shown that, with the right reforms, there is a path out of even more difficult fiscal situations than France’s.

We do not see continued sovereign bond pressure as a sufficiently powerful headwind to derail European equities en masse in 2025. A value bias in companies with strong free cash flow and solid balance sheets with earnings expectations that can be beaten ought to be able to navigate this scenario.

Where could Europe surprise positively in 2025?

Investor allocations and sentiment towards Europe are weak. Trump is seen as a serious threat either from tariffs and economic nationalism or from weaker support for Nato and Ukraine.

Trump’s victory and the promise of US deregulation and tax cuts have seen large investor allocations out of Europe and the rest of the world into the US, as shown by the movement in the currency market. But is this pessimism towards Europe justified? We list some potential upside catalysts that could cause capital to return to Europe in 2025.

1) A possible end to the Russo-Ukrainian war

Trump has made a bold promise that he could end the war in 48 hours when in office. He also sharply criticised the loss of life from the conflict. Zelensky has declared that Ukraine is open to the possibility of talks, and Trump and Zelensky had face-to-face discussions on 7 December in Paris.

Successful negotiations will depend on finding a suitable line on the Ukrainian map that both sides can accept. Russia has had recent momentum in taking territory but continues to sustain enormous casualties. Russia has also just suffered a severe blow in Syria that may weaken its hand in negotiations.

The deposition of Bashar Al-Assad in Syria may be significant for the war in Ukraine. Russia was desperate to keep Assad in power for several reasons. First, Russia keeps a naval base at the port of Tartus in Syria and an airbase forty miles north at Latakia. These military bases have enabled Russia to project power in the Mediterranean and Africa. The continued operation of these bases is now in question. Second, their intervention to prop up Assad from 2015-2018 gave the impression that Russia could act as a guarantor to other strongman rulers. Russia gained influence by providing guarantees to a number of rulers in the global south and gained support in return. After Assad’s fall, Russia’s guarantees have lost significant value.

Israel’s military intervention against Iran and its proxies also weakens Russia. Iran used Syria as its land bridge to Hezbollah in Lebanon. Iran’s biggest investments in the region were Syria under Assad and Hezbollah, and they have both been hobbled.

Iran’s position is now so weak and its economy so fragile that it seems to be seeking to improve relations with the West. Iran’s new president, Masoud Pezeshkian, has formally declared that he is “ready to engage” with the West on its nuclear programme and pursue peace so that sanctions can be lifted and its economy recover. Part of the West’s preconditions for Iran will likely demand a reduction in support for Russia. Without forceful Iranian support, Russia will be further marginalised and see lower weapons deliveries.

It is impossible to know if the Ukrainian war will end, but the odds of some kind of truce are rising. Any kind of peace will see some relief in Europe, with a large Ukrainian reconstruction to follow, supporting economic growth. Precautionary savings rates are very high in nearby countries like Germany and Poland, and the end of the war could see consumer confidence recover.

2) A new German government led by Friedrich Merz

Germany will have a new Chancellor on 23 February and the most likely candidate is Friedrich Merz. Merz is the leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and he will ruthlessly support German economic and military interests. The CDU will likely need to be in a coalition with either the Greens or the Social Democratic Party, but the CDU will be the dominant power and will lead the legislative agenda.

Germany has the second highest electricity costs in the world and Merz is keen to tackle this. He is likely to restart three nuclear power stations in Germany and begin investing in small modular reactors. He is also likely to cut subsidies for renewable energy.

Merz also has an intention to lower corporation tax and reduce social security payments. The German benefit system, Bürgergeld, is very generous, disincentivising work for parts of the population. Merz is set to reform the benefits system and make changes to pensions by adjusting levels of taxation by age to incentivise people to work longer.

He will aim to maintain Germany’s debt brake but will redirect government savings into infrastructure and defence investments.

Merz’s overall message is similar to Trump’s – lower energy prices, reduce regulation, lower clean energy subsidies, incentivise work and lift growth. The difference with the US is that Germany has even more levers to pull. We expect Merz to begin to change global investor attitudes towards Germany and potentially drive increased allocations to European equities.

3) Stronger Chinese consumption in 2025

Much has been written about China’s stimulus, but the main takeaway is that China is performing Quantitative Easing (QE). The major departure from past stimulus is that China is now targeting asset prices, in particular equity, bond and property prices. The People’s Bank of China is now buying equities and government bonds and the state is starting to buy property and reduce unsold inventory.

Just as we saw with the Fed and the ECB’s QE following the financial crisis, the ability of asset purchases to lift GDP is limited, but QE has been shown to be powerful with respect to asset prices.

Property prices are a key metric for Chinese consumer confidence. Chinese property prices peaked in September 2021 and are down 13% in nominal terms and 15% in real terms since then. In the 20 years prior to the peak, prices had risen steadily at a 4.2% compound annual growth rate.

Given that the majority of consumer wealth is invested in property, these absolute price declines have significantly dented consumer spending and helped drive up the Chinese savings rate.

Chinese households now have savings deposits above $20tn. In recent years, term deposit balances have jumped as consumption has been deferred.

Chinese bond yields have also fallen sharply over the last year, with the 10-year now below 2%. The combination of lower interest rates and the state buying unsold housing inventory could stop the decline in Chinese house prices in 2025. This may improve Chinese consumer confidence and spending compared to expectations, which could benefit European industry.

4) Europe is trading at a record discount to the US, meaning the hurdle to outperform is low

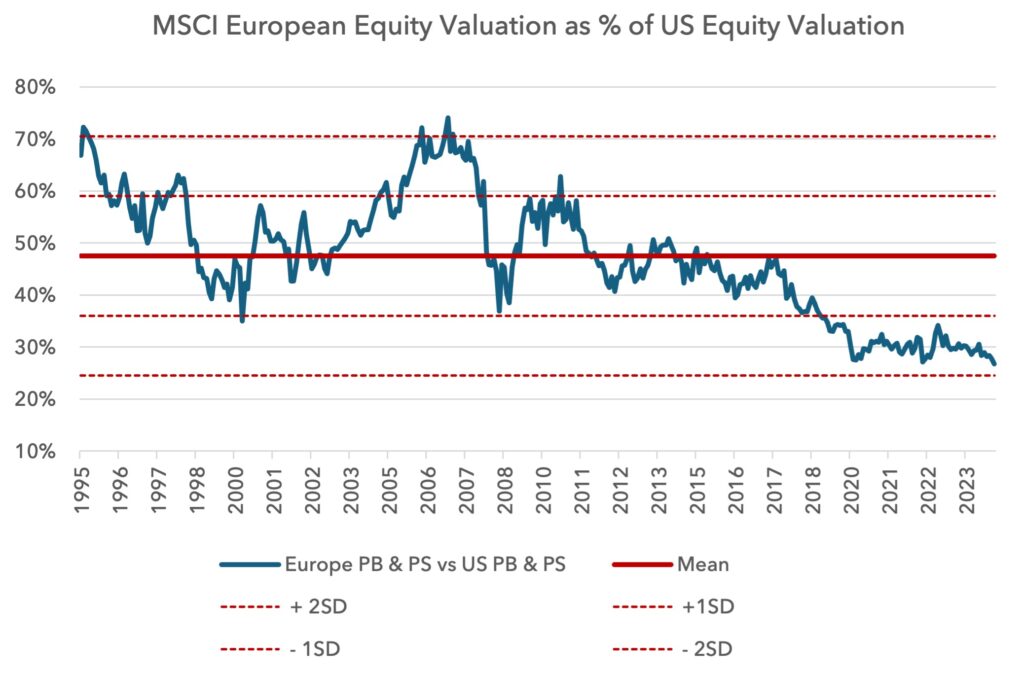

European equities are trading at a large discount to the US, as we show below. Whilst this was also the case a year ago, the discount is even larger today, and investor expectations have changed, with investors close to euphoric when it comes to US prospects. This contrasts with pessimism towards Europe.

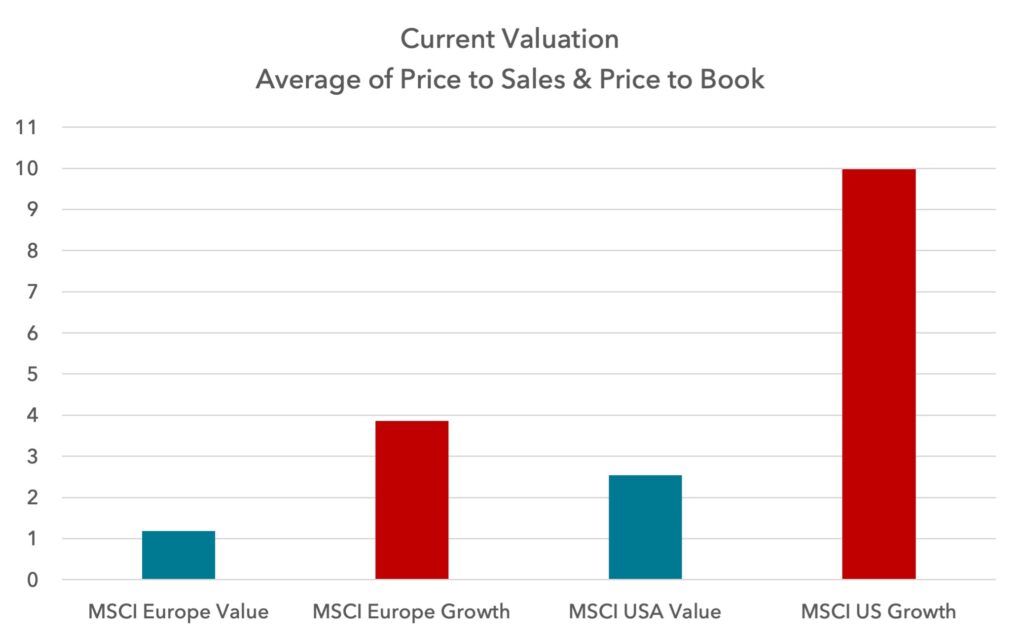

US value is at a 115% premium to European value, with US growth at a 160% premium.

Whilst European equities have tended to be cheaper than US equities over the last 30 years, we are at a record discount today. Below we show a chart that takes the average of Europe’s price to sales and price to book and compares that with the US since 1995. Europe’s mean valuation over the period is just under 50% of the US, but today it is at 26%, which is close to two standard deviations cheaper and a record low.

If European equities were to return to their 30 year average discount to the US, they could outperform the US by 77%. If Europe was to return to its relative valuation in 2007, it could outperform by over 160%.

If European equities were to return to their 30 year average discount to the US, they could outperform the US by 77%. If Europe was to return to its relative valuation in 2007, it could outperform by over 160%.

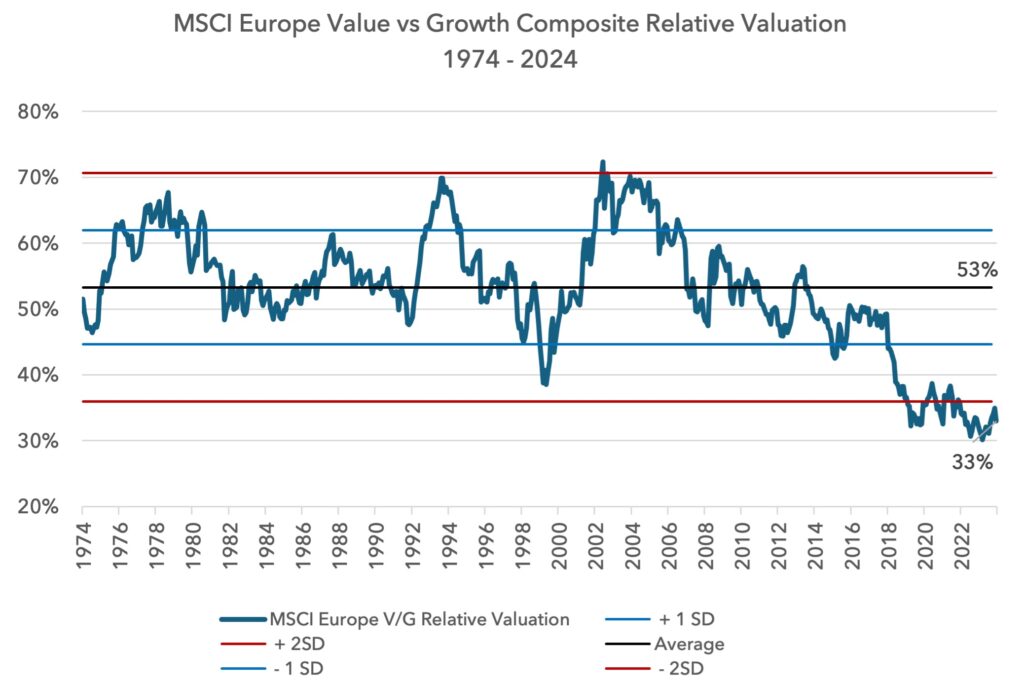

Within European equities, value is clearly the most compelling, trading at a large discount to European growth equities.

European value is supported twice over: not only is Europe a cheap region, but value is especially cheap within it.

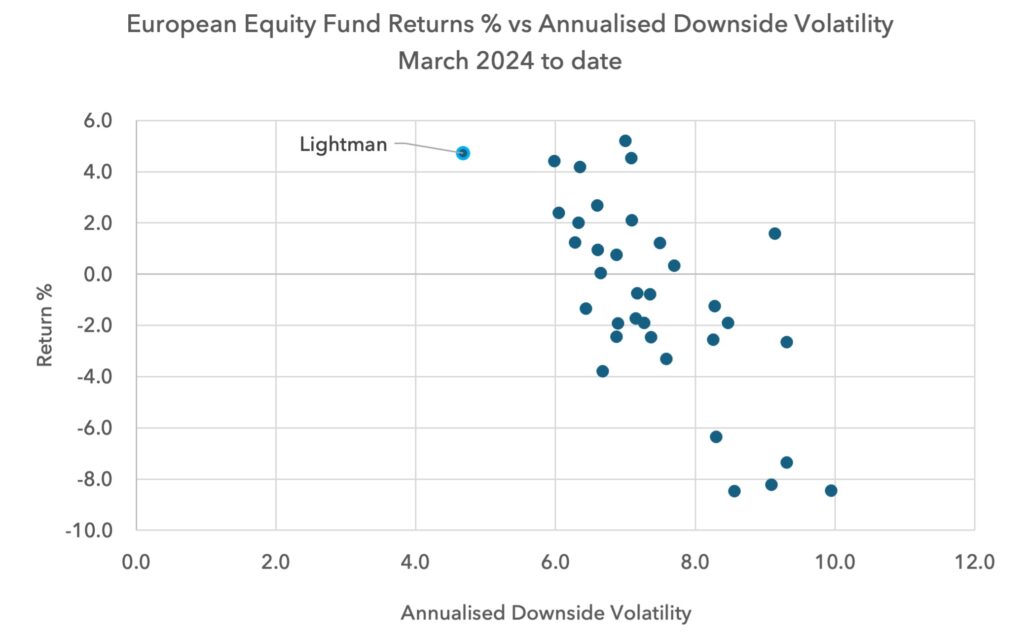

This cheapness might be explaining why European value is showing improving risk-adjusted returns. Following on from our recent notes on the low downside volatility for value compared to growth, we show below our portfolio compared to the 35 largest funds in the peer group. The portfolio’s relative performance started to improve in early March this year – we show the return compared to the downside volatility from this date.

This cheapness might be explaining why European value is showing improving risk-adjusted returns. Following on from our recent notes on the low downside volatility for value compared to growth, we show below our portfolio compared to the 35 largest funds in the peer group. The portfolio’s relative performance started to improve in early March this year – we show the return compared to the downside volatility from this date.

5) Flows are getting very full in the US, raising the risks of a reversal, whilst European flows have been low

5) Flows are getting very full in the US, raising the risks of a reversal, whilst European flows have been low

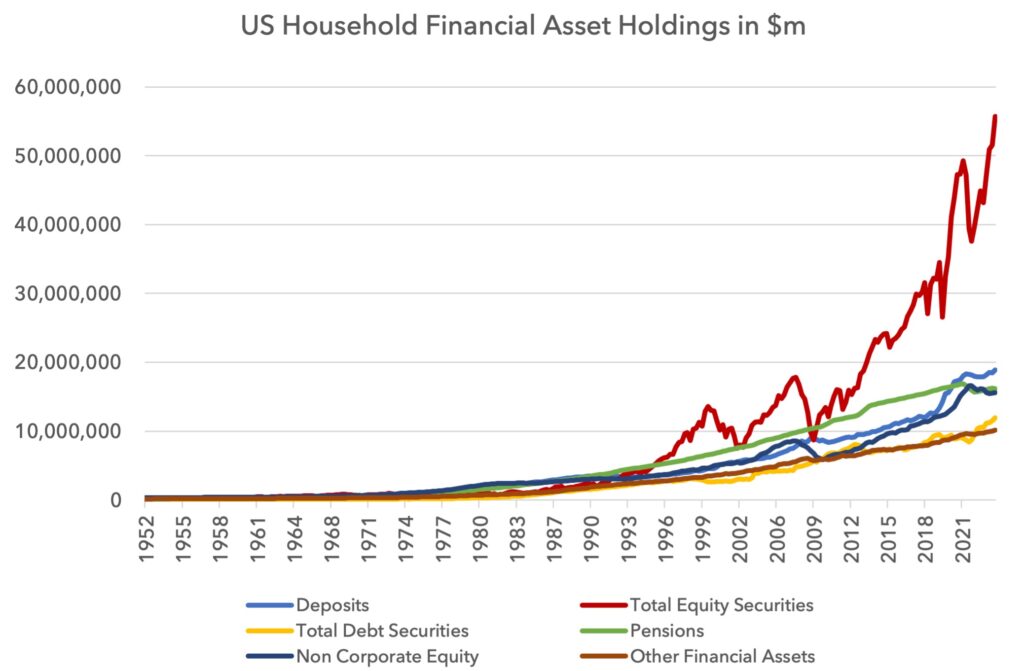

When assessing investor flows with a long-term perspective, the Federal Reserve’s Z1 Flow of Funds can be helpful. With data starting in 1952, it is possible to monitor total allocations of US households by financial instrument. As shown below, equities have had a huge run over the past decade and dwarf allocations to all other financial assets.

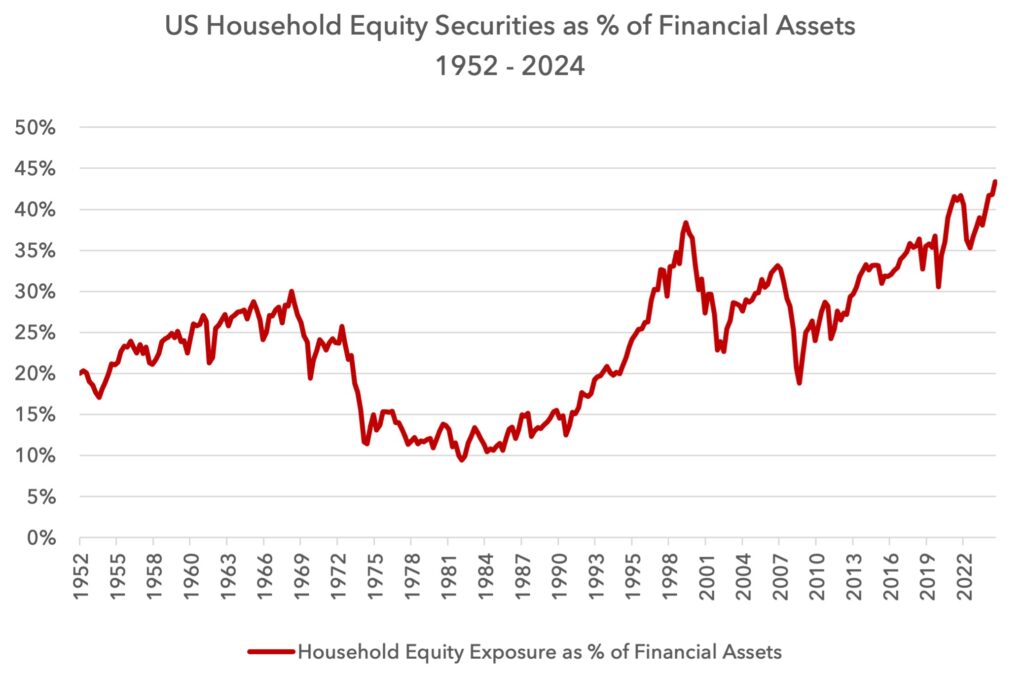

It is perhaps more helpful to monitor equity allocations as a percentage of financial assets, which is shown below. US equities now take a higher allocation than during the peak of the dot-com boom. This high allocation does not guarantee a reversal of flows, but it suggests we might be in the late innings of the US equity market cycle, at least in relative performance terms.

It is perhaps more helpful to monitor equity allocations as a percentage of financial assets, which is shown below. US equities now take a higher allocation than during the peak of the dot-com boom. This high allocation does not guarantee a reversal of flows, but it suggests we might be in the late innings of the US equity market cycle, at least in relative performance terms.

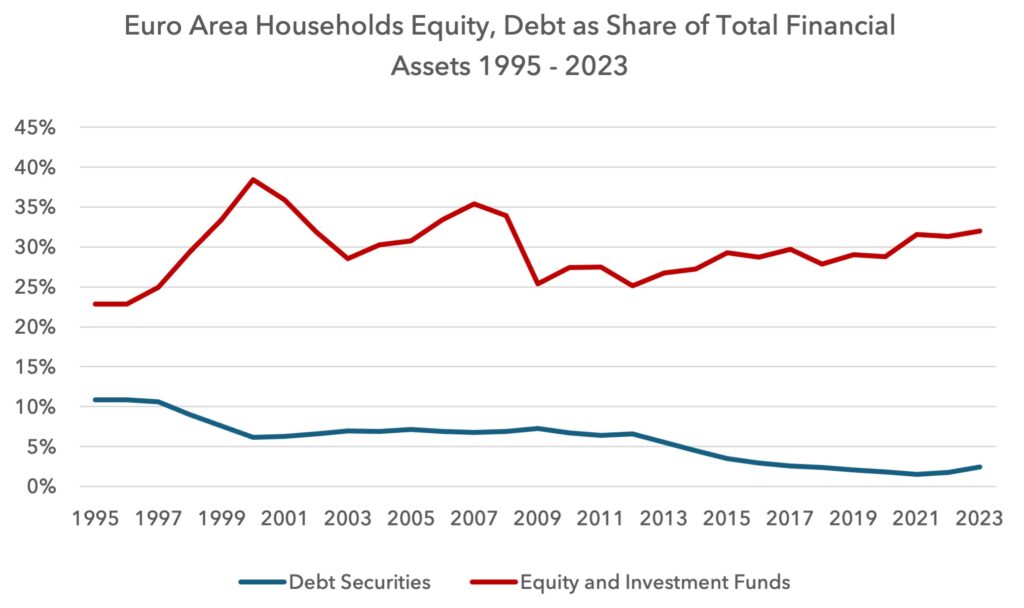

European data is not as detailed, uses different definitions and does not go back as far. Eurostat shows European household allocations to equities since 1995 and the picture is pretty muted.

European data is not as detailed, uses different definitions and does not go back as far. Eurostat shows European household allocations to equities since 1995 and the picture is pretty muted.

Trump may well be bullish for European equities

Whilst Europe may face more sovereign debt-related pressures in 2025, we do not see this hindering the investment case for the region. Active management with a value bias, with some tactical caution on some European financials, ought to be able to navigate this scenario.

Trump’s own economic nationalism is likely to push Europe and China to support their own economic growth more forcefully. In this way, Trump might help markets in other parts of the world. Europe, in particular, has willingly pursued energy and regulatory policies that have stifled growth. This may begin to change in 2025, led by Merz in Germany.

A truce in the war in Ukraine and a potential peace dividend could also drive investors to return to the region.

Whilst Trump’s policies may be bullish for US long-term economic growth, they are likely to be highly disruptive to the economy and potentially to markets for the first year or two. Sharp reductions in government spending are likely to slow the economy in the early stages at a minimum.

We would expect European equities to outperform the US in 2025. Expectations, valuations and positioning suggest the US has a high hurdle to overcome. Europe in contrast has low expectations, low valuations and low allocations.

We are cautiously optimistic about the potential for our absolute and relative returns in 2025. Our portfolio’s median price to earnings ratio in 2025 is 12.4 with a price to sales ratio of 1.4. The forecast dividend yield is 4.8% in 2025 and 5.1% in 2026.

Sources:

IMF Fiscal Monitor Database, US Department of the Treasury - Treasury International Capital System (TIC), People’s Bank of China, Strategas, Metzler, PRC Macro, Lightman Investment Management

Legal

Disclaimer

This communication and its content are owned by Lightman Investment Management Limited (“Lightman”, “we”, “us”). Lightman Investment Management Limited (FRN: 827120) is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (“FCA”) as a UK MiFID portfolio manager eligible to deal with professional clients and eligible counterparties in the UK. Lightman is registered with Companies House in England and Wales under the registration number 11647387, having its registered office at c/o Buzzacott LLP, 130 Wood Street, London, United Kingdom, EC2V 6DL.

Target audience

This communication is intended for ‘Eligible Counterparties’ and ‘Professional’ clients only, as described under the UK Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (“FSMA”) (and any amendments to it). It is not intended for ‘Retail’ clients and Lightman does not have permission to provide investment services to retail clients. Generally, marketing communications are only intended for ‘Eligible Counterparties’ and ‘Professional’ clients in the UK, unless they are being used for purposes other than marketing, such as regulations and compliance etc. The Firm may produce marketing or communication documents for selected investor types in non UK jurisdictions. Such documents would clearly state the target audience and target jurisdiction.

Collective Investment Scheme(s)

The collective investment scheme(s) – WS Lightman Investment Funds (PRN: 838695) (“UK OEIC”, “UK umbrella”), and WS Lightman European Fund (PRN: 838696) (“UK sub-fund”, “UK product”) are regulated collective scheme(s), authorised and regulated by the FCA. In accordance with Section 238 of FSMA, such schemes can be marketed to the UK general public. Lightman, however, does not intend to receive subscription or redemption orders from retail clients and accordingly such retail clients should either contact their investment adviser or the Management Company Waystone Management (UK) Limited (“Waystone UK”) in relation to any fund documents.

The collective investment scheme(s) - Elevation Fund SICAV (Code: O00012482) (“Luxembourg SICAV”, “Luxembourg umbrella”), and Lightman European Equities Fund (Code: O00012482_00000002) (“Luxembourg sub-fund”, “Lux product”) are regulated undertakings for collective investments in transferrable securities (UCITS), authorised and regulated by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF) in Luxembourg. In accordance with regulatory approvals obtained under the requirements of the Law of 17 December 2010 relating to undertakings for collective investment, the schemes can be marketed to the public in Luxembourg, Norway, Spain, and Republic of Ireland. Lightman, however, does not intend to receive subscription or redemption orders from any client types for the Lux product and accordingly such client should either contact a domestic distributor, domestic investment advisor or the Management Company Link Fund Solutions (Luxembourg) S.A. (“Link Luxembourg”) in relation to any fund documents.

Luxembourg umbrella and Luxembourg sub-fund are also approved for marketing to professional clients and eligible counterparties in the UK under the UK National Private Placement Regime (NPPR). UK registration numbers for the funds are as follows: Elevation Fund SICAV (PRN: 957838) and Lightman European Equities Fund (PRN: 957839). Please write to us at compliance@lightmanfunds.com for proof of UK registration of the funds.

Luxembourg sub-fund is also approved for marketing to qualified investors in Switzerland, within the meaning of Art. 10 para. 3 and 3ter CISA. In Switzerland, the representative is Acolin Fund Services AG, Leutschenbachstrasse 50, 8050 Zurich, Switzerland, whilst the paying agent is NPB Neue Privat Bank AG, Limmatquai 1 / am Bellevue, 8024 Zurich, Switzerland.

Accuracy and correctness of information

Lightman takes all reasonable steps to ensure the accuracy and completeness of its communications; we however request all recipients to contact us directly for the latest information and documents as issued documents may not be fully updated. We cannot accept any liability arising from loss or damage from the use of this communication.

Wherever our communications refer to a third party such as Waystone, Link, Northern Trust etc., we cannot accept any responsibility for the availability of their services or the accuracy and correctness of their content. We urge users to contact the third party for any query related to their services.

Important information for non-UK persons (Including US persons)

This communication is not intended for any person outside of the UK, Switzerland, or the European Economic Area (EEA). Lightman or any of the funds referenced in this communication are not approved for marketing outside of the UK, Switzerland, or the EEA. All such persons must consult their domestic lawyers in relation to services or products offered by Lightman.

Risk warning to all investors

The value of investments in any financial assets may fall as well as rise. Investors may not get back the amount they originally invested. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance. Potential investors should not use this communication as the basis of an investment decision. Decisions to invest in any fund should be taken only on the basis of information available in the latest fund documents. Potential investors should carefully consider the risks described in those documents and, if required, consult a financial adviser before deciding to invest.

Offer, advice, or recommendation

No information in this communication is intended to act as an offer, investment advice or recommendation to buy or sell a product or to engage in investment services or activities. You must consult your investment adviser or a lawyer before engaging in any investment service or product.

GDPR

Lightman may process personal information of persons using this communication. Please read our privacy policy.

Copyright

This communication cannot be distributed or reproduced without our consent.